Two Dogs Foraging

In 1985, ITN filmed Inner City Drugs in the West Granton Housing Estate, North Edinburgh, capturing interviews with residents about life in the area and the impact of drug addiction. Two Dogs Foraging draws on this archival footage, using auto-text generated during the digitisation process to craft its narrative. By deliberately retaining and repurposing these automated descriptions, the work highlights the disconnection between digital archiving and lived experiences. Created using a letterpress - a traditional technique - it juxtaposes the tactile nature of print with the impersonal digital age, re-evaluating how language portrays signs of deprivation. Developed in collaboration with independent Oxford-based printer Ricard Lawrence, the work challenges perceptions of documentation and memory, urging reflection on the ways technology shapes our understanding of social issues.

Beyond Man & Time

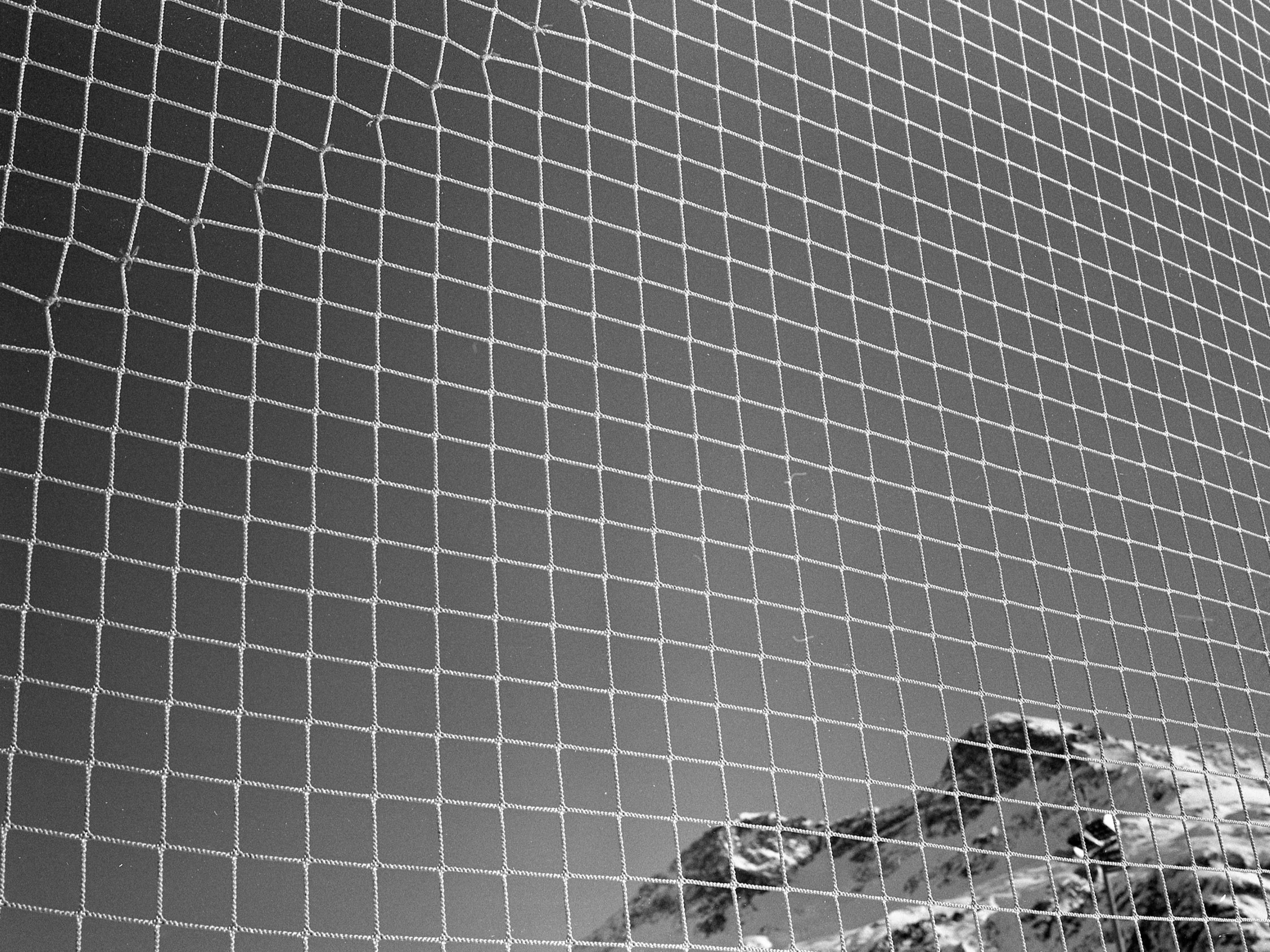

Inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885), Beyond Man & Time explores the interplay of vast landscapes, solitude, and the enigma of existence. This modern visual record traces Nietzsche’s wanderings in Sils Maria, Switzerland, illuminating the metaphysical and ethical significance of his ideas. Central to the work is Zarathustra’s retreat into the mountains, described as ‘6,000 feet beyond man and time’, embodying Nietzsche’s concept of eternal recurrence and humanity’s search for purpose. Through photographic landscapes and portraits, the project deepens our understanding of the profound connection between Nietzsche’s philosophy and the transformative power of these settings.

Valley of the Flowers

The Bozeman Trail was a vital overland route linking Montana’s gold rush territory to the Oregon Trail, active primarily from 1863 to 1868. Its path through Wyoming crossed lands held by Native American tribes, sparking conflict and eventual warfare. The Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, newly arrived to the region, resisted the influx of pioneers and settlers, which was sanctioned under the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. Although the treaty granted the Crow Indians rights to the contested area, the U.S. Army launched campaigns to secure the trail, disregarding Native claims to their homeland. The Valley of the Flowers, named after the city of Bozeman, reflects on this history through a contemporary lens, exploring themes of racial segregation and land ownership. Captured on film, and using a purposefully slower process, the project deepens engagement with the landscape and its layered, often turbulent, history.

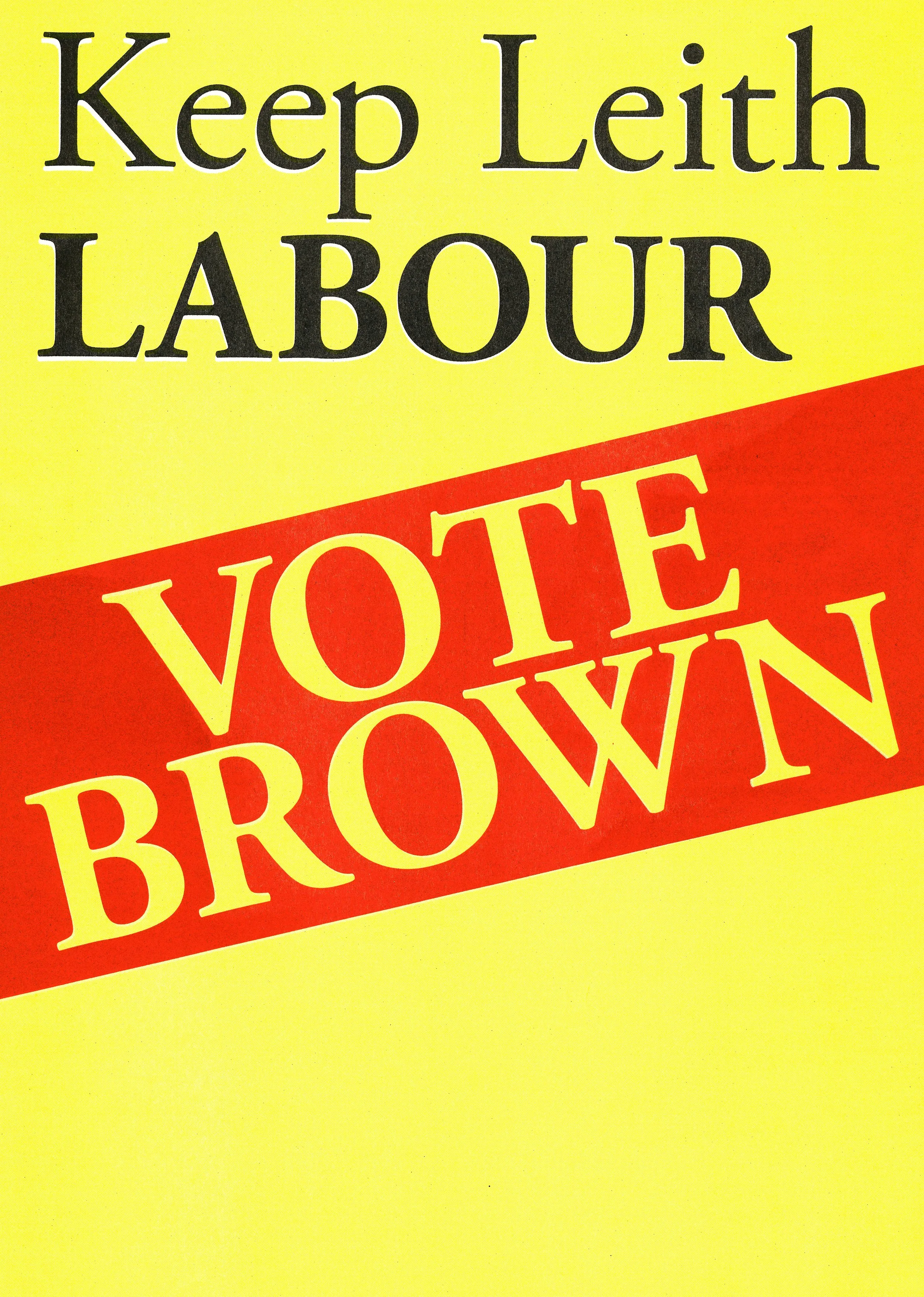

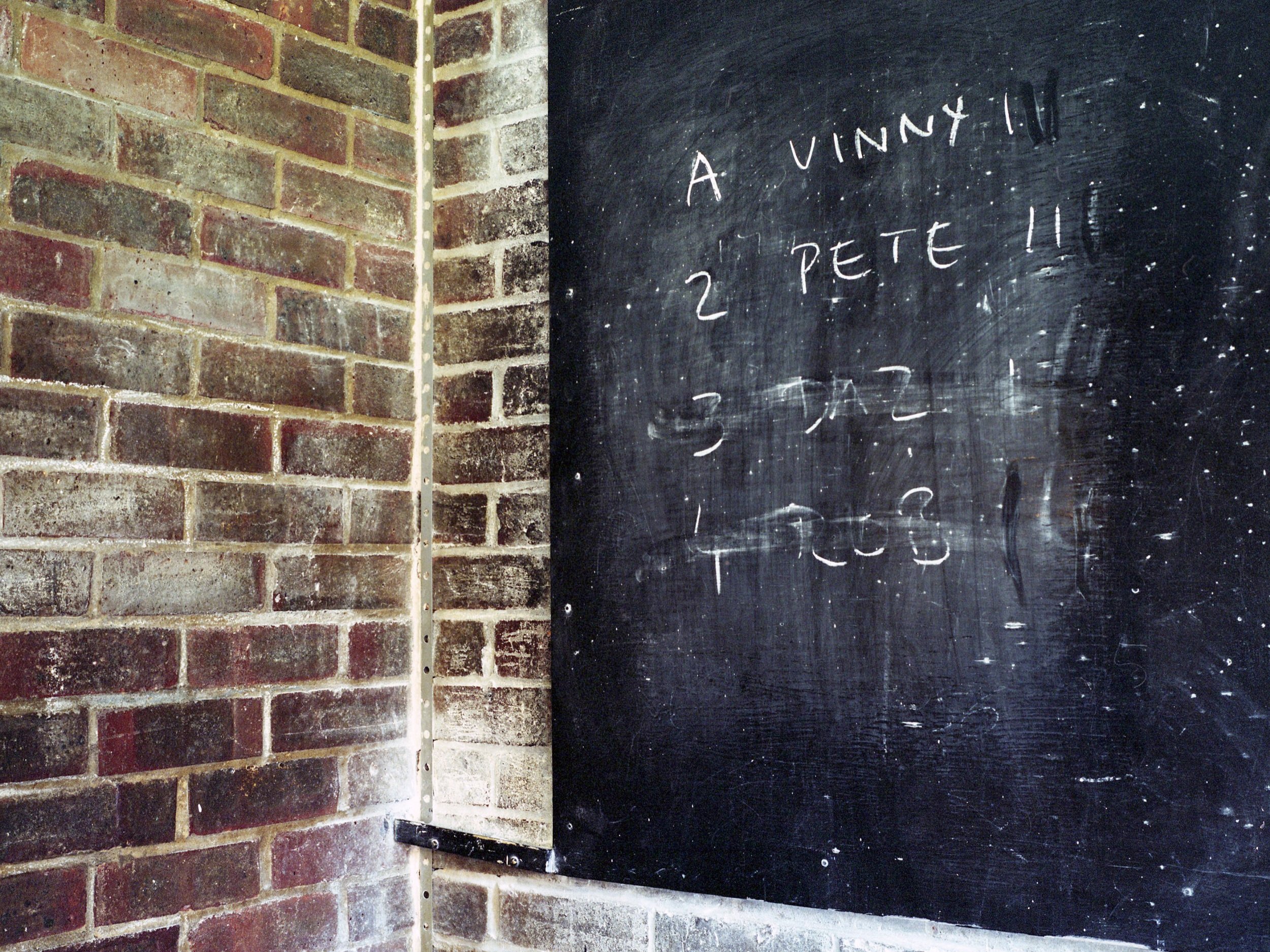

Keep Leith Labour

Inspired by Graham MacIndoe’s 1986 archival photograph Pilton, Edinburgh, the work reflects on everyday life of Edinburgh’s 1980’s political undercurrents. MacIndoe’s image features a subject holding a “KEEP LEITH LABOUR” sign in the notorious Pilton housing scheme of North Edinburgh, which connects to Ron Brown, Leith’s MP and a fervent anti-poll tax campaigner. Despite ridicule from the media and parliamentary establishment, Brown and his wife May courageously championed causes others avoided, standing firmly for Leith’s residents. KEEP LEITH LABOUR revisits the symbolism used to rally Pilton and North Edinburgh voters to Labour. Redesigned by the artist, and printed on a risograph machine from Out of the Blue in Leith, the work explores the use of colour in political campaigns and reinterprets archival materials, offering a modern perspective on the power of design in shaping political identity and community solidarity.

On-Sea

In 1974, the posthumous publication A Day Off: An English Journal unveiled the work of English photographer Tony Ray-Jones, who captured the unique ways the English spend their leisure time. Divided into chapters such as The Seaside, Summer Carnivals, Dancers, London, and Society, the collection reflects Ray-Jones’s artistic journey from a Yale scholarship to street photography in New York City, and his return to Britain in 1965. Fascinated by English identity, Ray-Jones compiled detailed lists of locations he believed epitomized this identity, with a particular emphasis on the seaside. His notebooks, now preserved at the National Media Museum in Bradford, include a list of seaside towns, where he marked off visited locations. Tragically, Ray-Jones was diagnosed with leukemia in late 1971 and died on March 13, 1972, aged just 30. On-Sea honors his vision by photographing seaside towns he listed but never captured, exploring their people and landscapes anew.

Martello Court

Muirhouse has long been burdened by negative labels (such as notorious, violent, and deprived), and often viewed as a blight on Edinburgh and a place best ignored. Dominated by the stark, Soviet-style Martello Court, a 200-foot, 23-story tower synonymous with the area’s struggles, Muirhouse has been a focal point for social challenges. Nearly thirty years ago, photographer John Sturrock chronicled the community during the Positive Lives - Responses to HIV project, exposing issues like poverty, crime, drugs, and disease, while also capturing the resilience and camaraderie of its residents. More recently, Document Scotland has featured Yoshi Kametani’s vibrant and wry portraits and Paul Duke’s No Ruined Stone, which balanced realism with hope. In 2020, amid the hardships of lockdown, Martello Court explores life in Muirhouse, reflecting on the persistent stereotypes that shaped his own perceptions of the area.

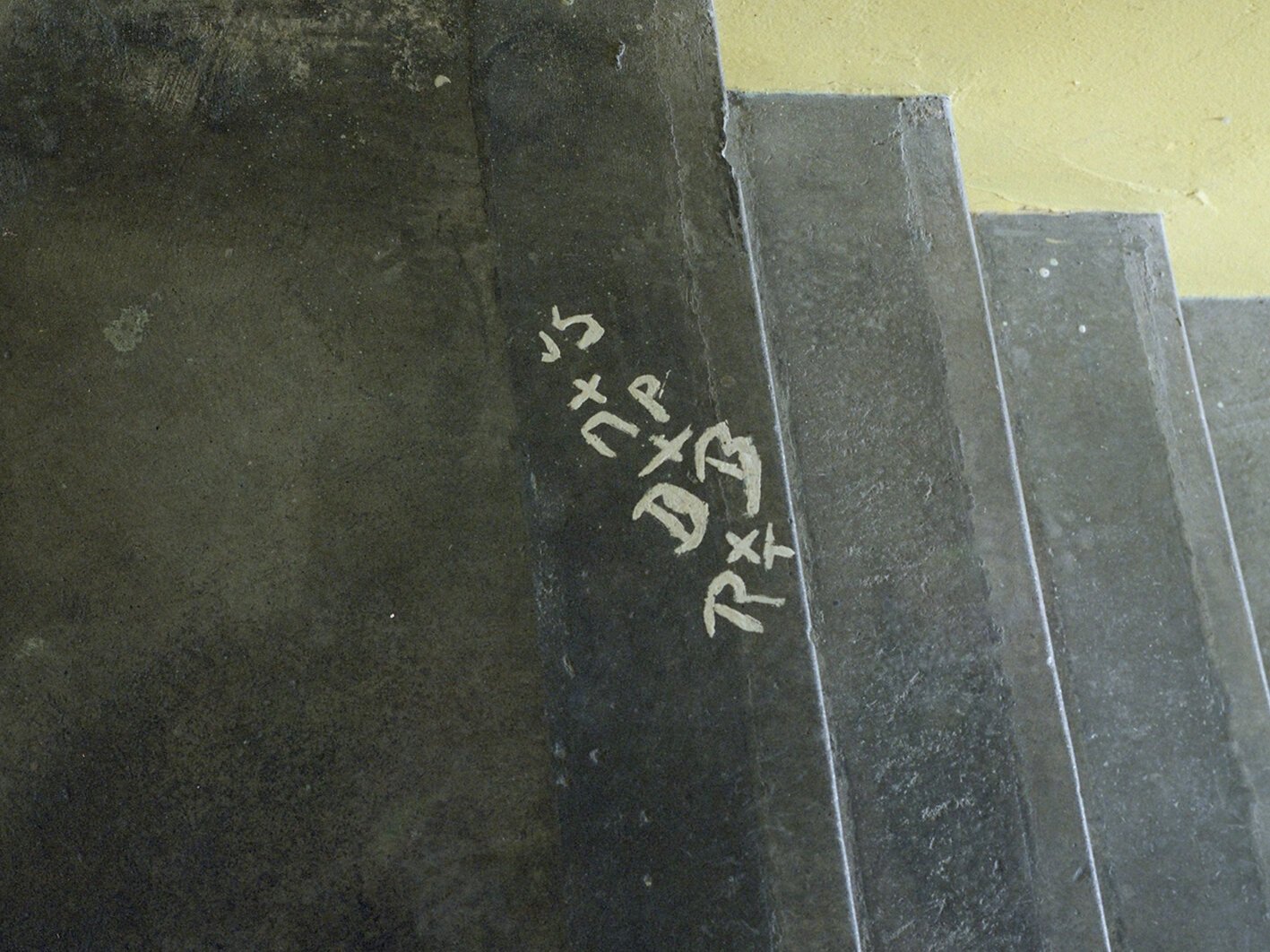

YLT

In February 2024, an array of street signs appeared in the Leith and Newhaven areas of Edinburgh. At first glance, these signs resembled standard traffic management signage, but closer inspection revealed a striking difference. Edinburgh council chiefs confirmed that these signs were not official, instead referencing YLT, or the Young Leith Team, a notorious street gang. By analysing and recreating these signs, the project explores how symbols associated with gang culture can be deconstructed and reframed within an artistic context. This process not only investigates the visual language of subcultures but also examines how illicit imagery can be reinterpreted to foster dialogue about its cultural and social impact. Through this transformation, the work challenges traditional notions of authority, creativity, and the boundaries between urban intervention and art.

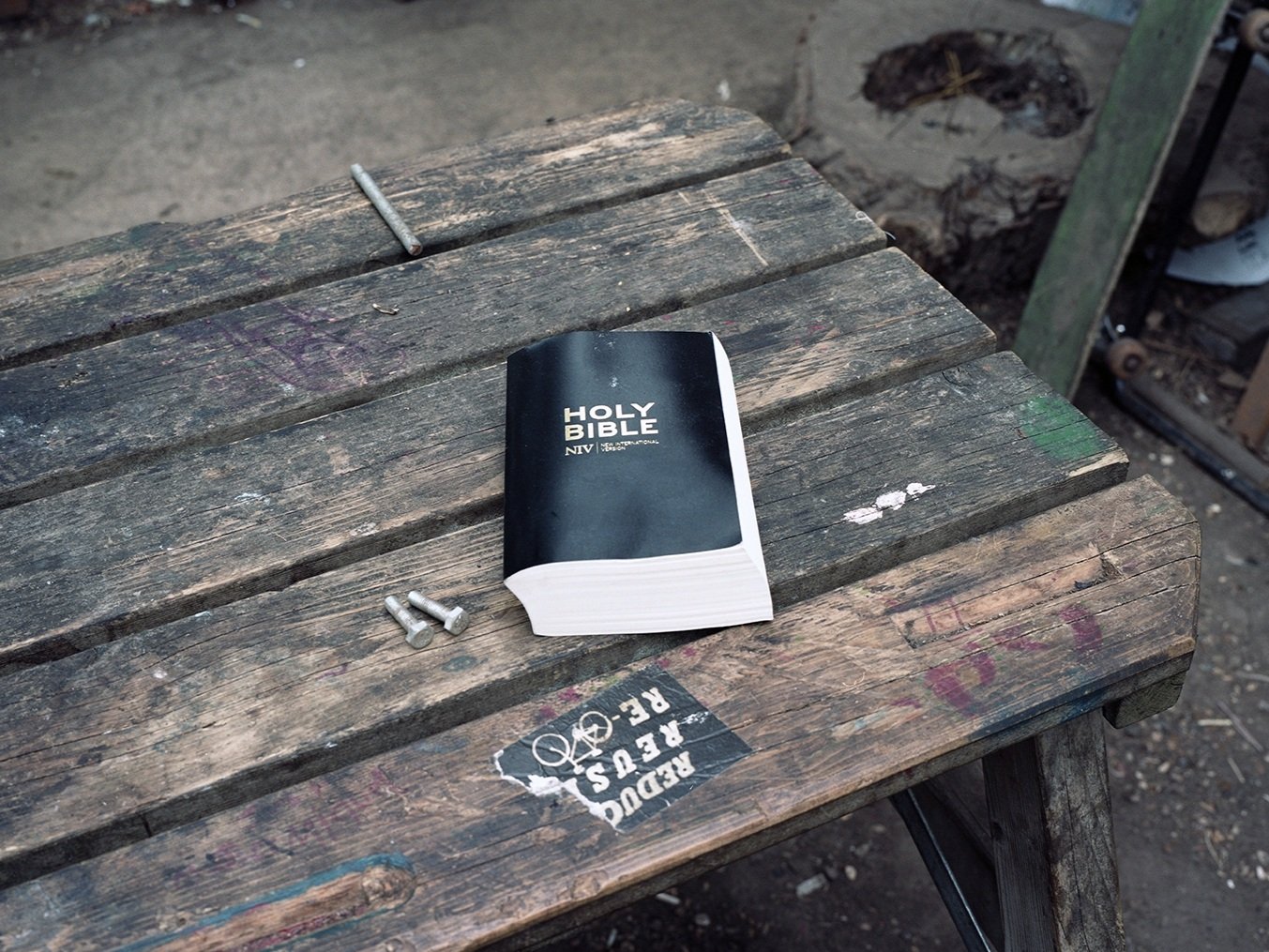

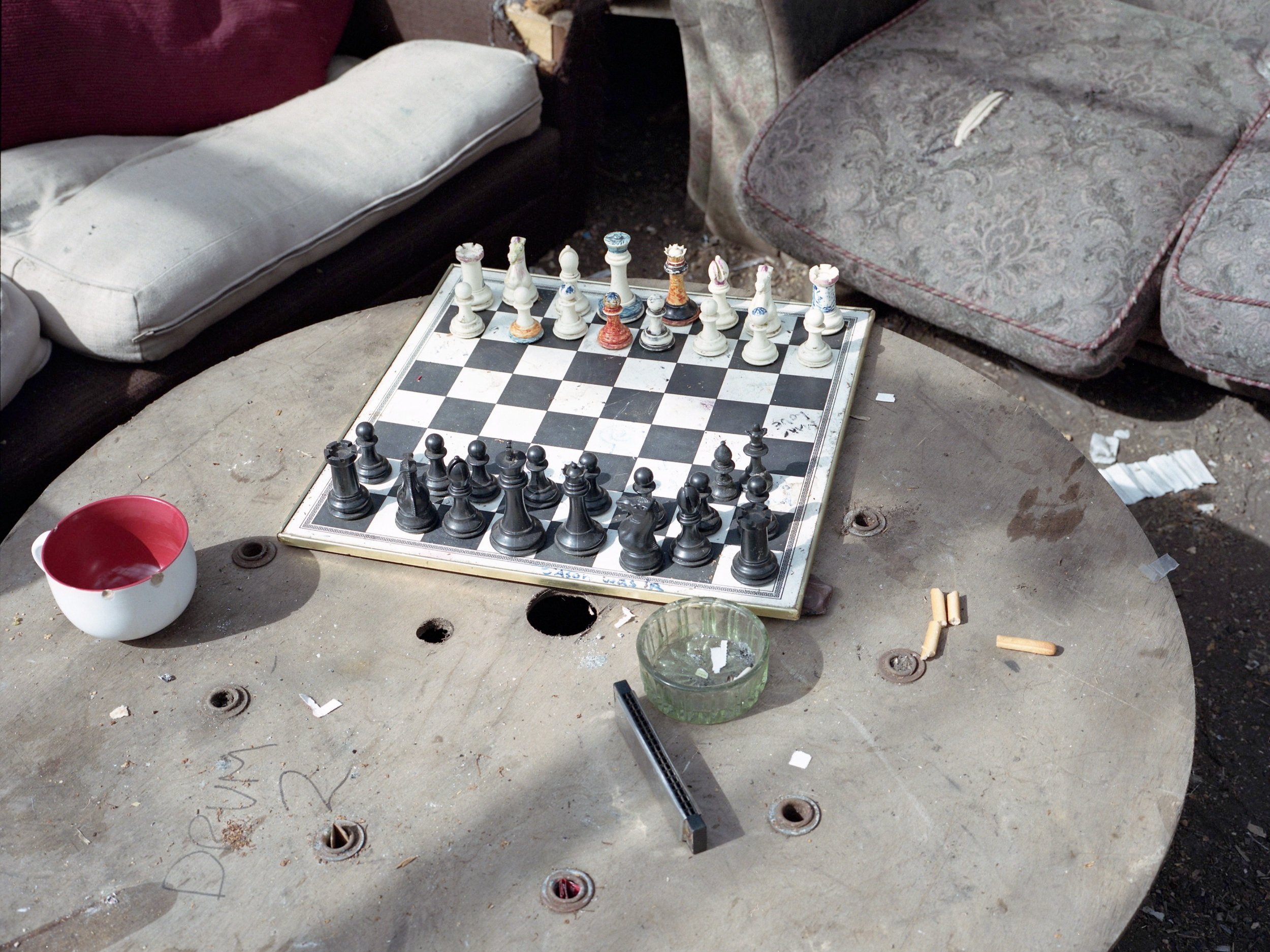

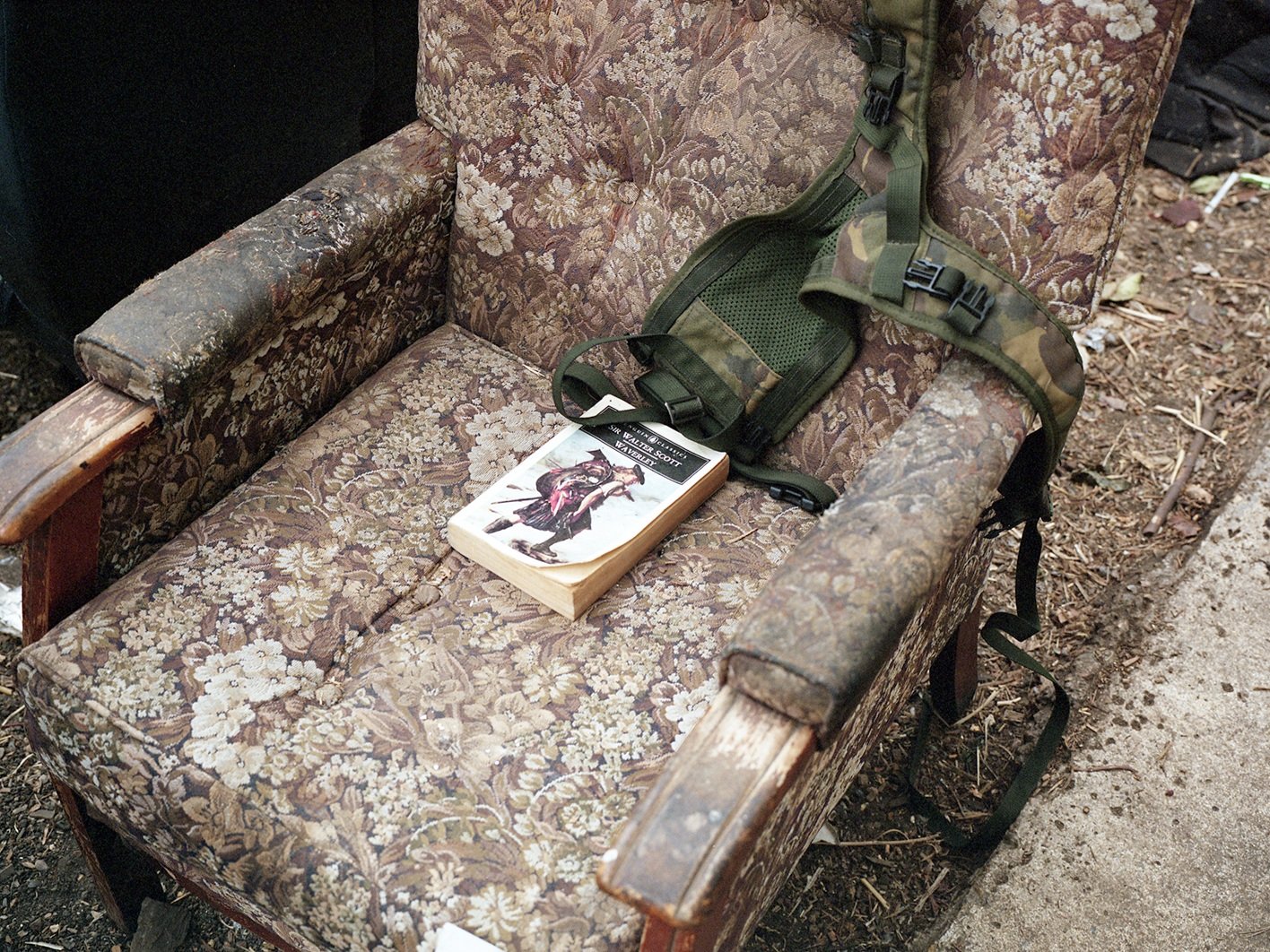

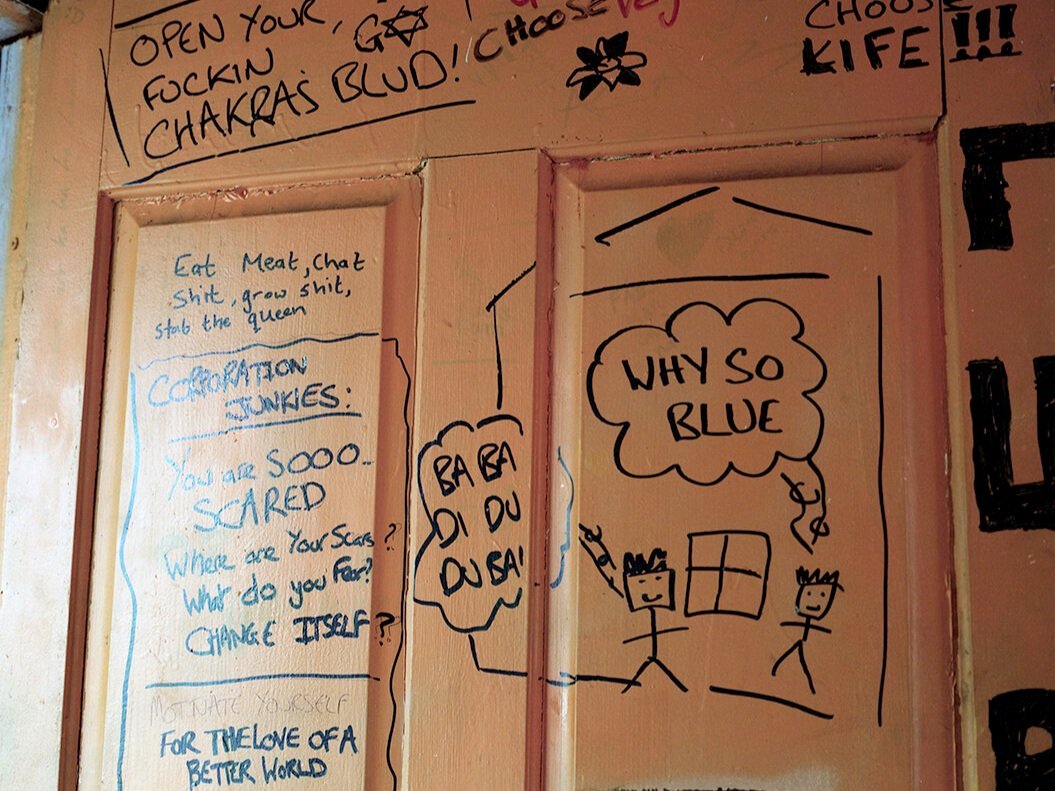

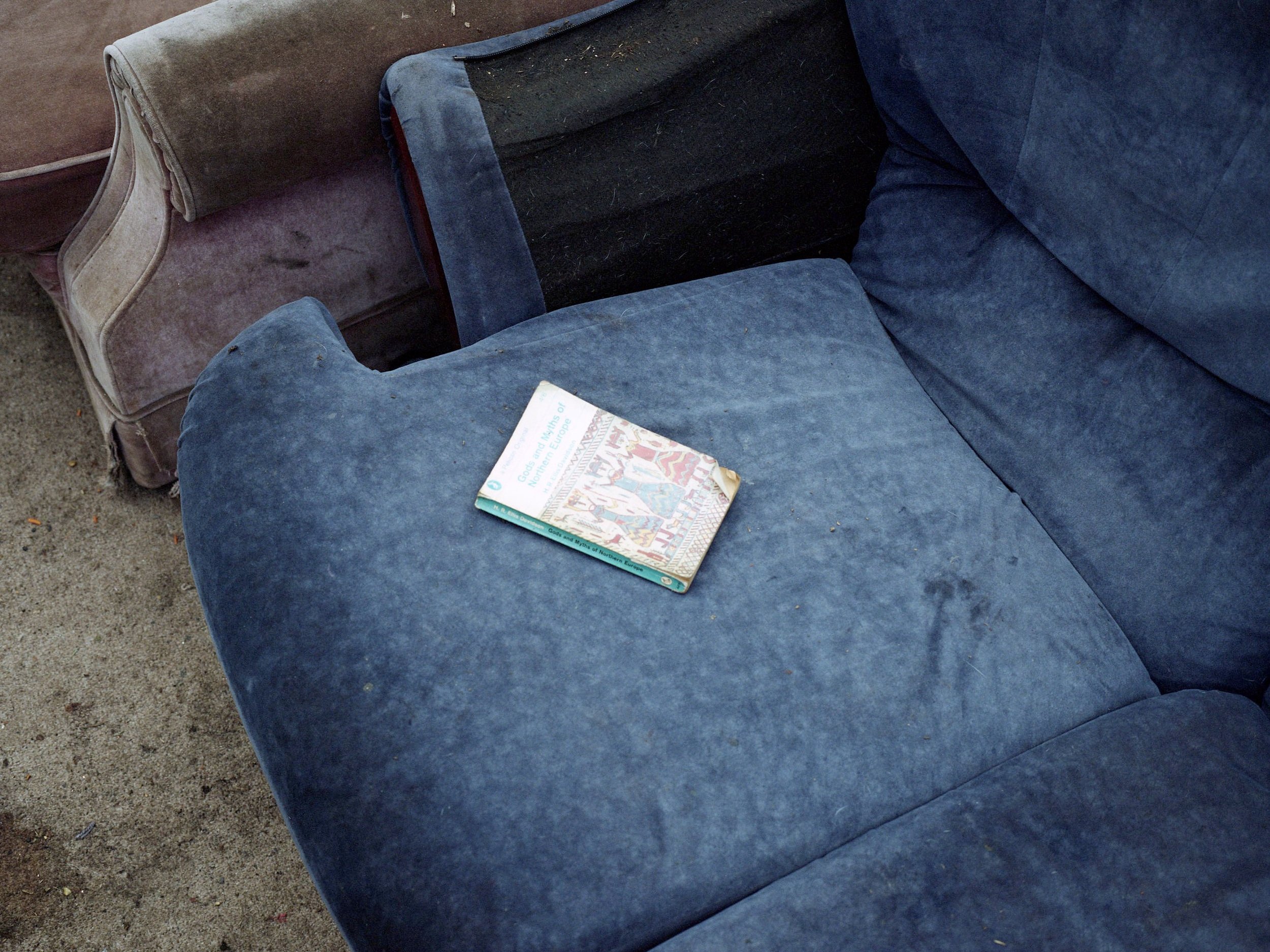

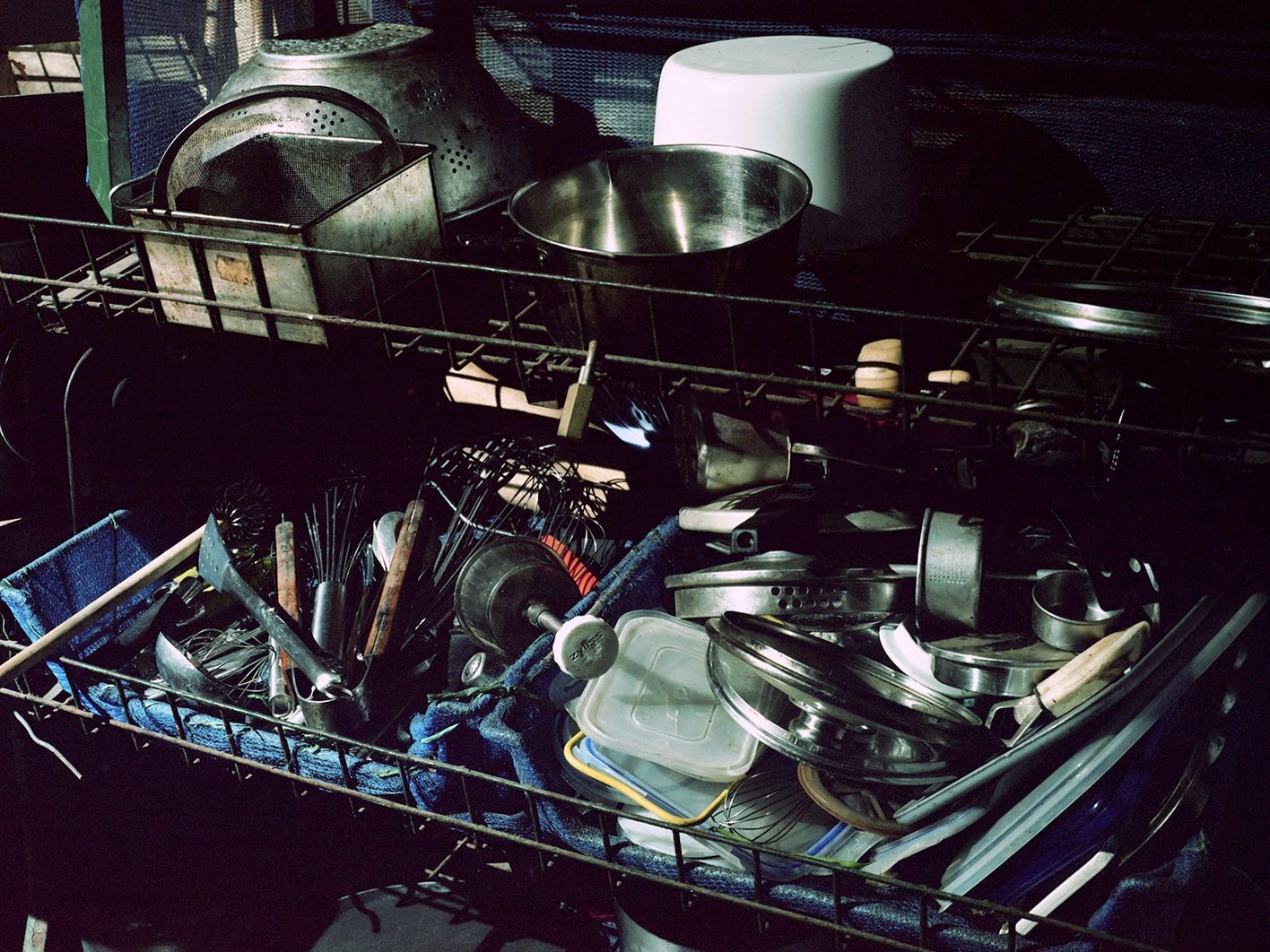

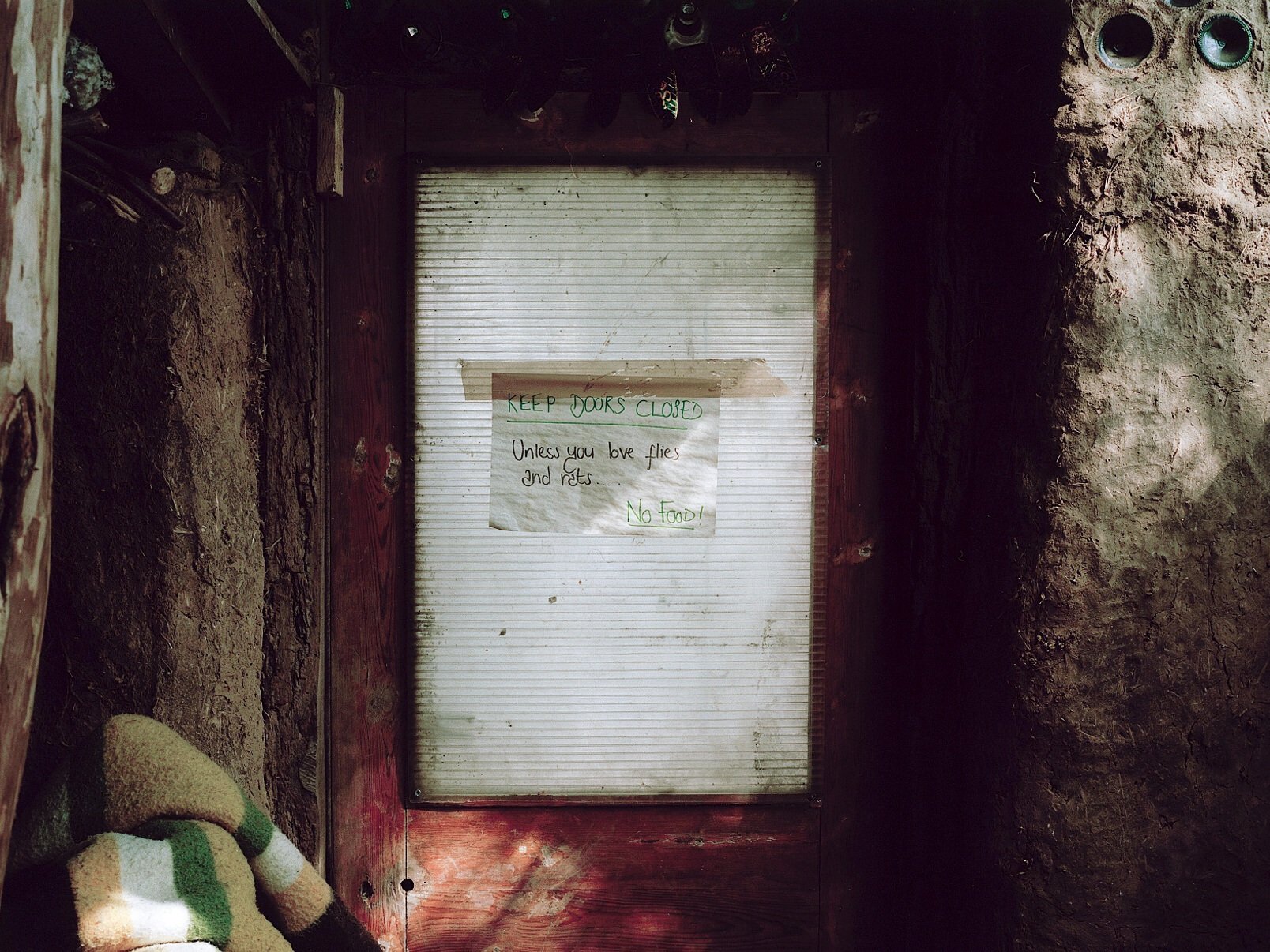

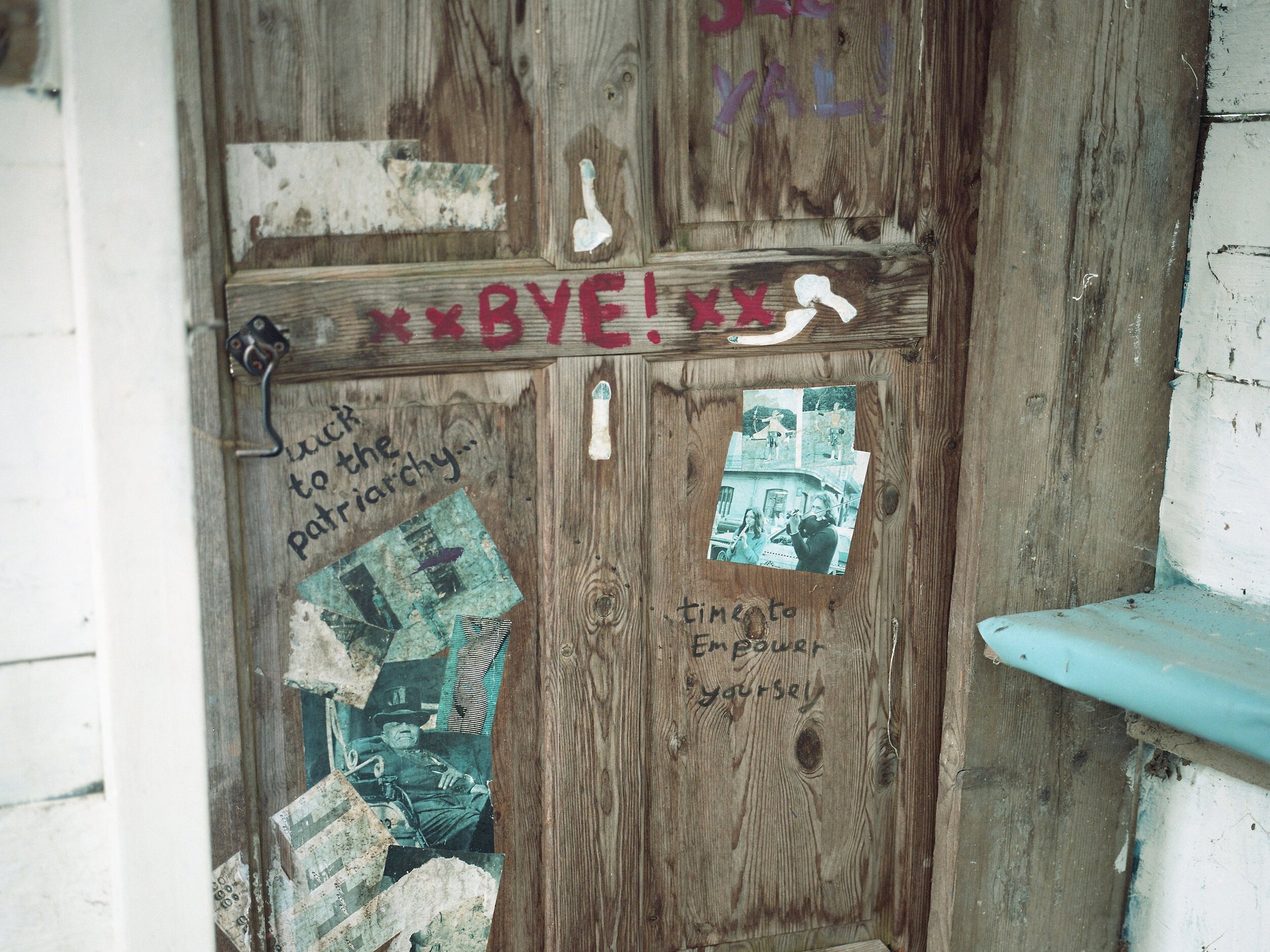

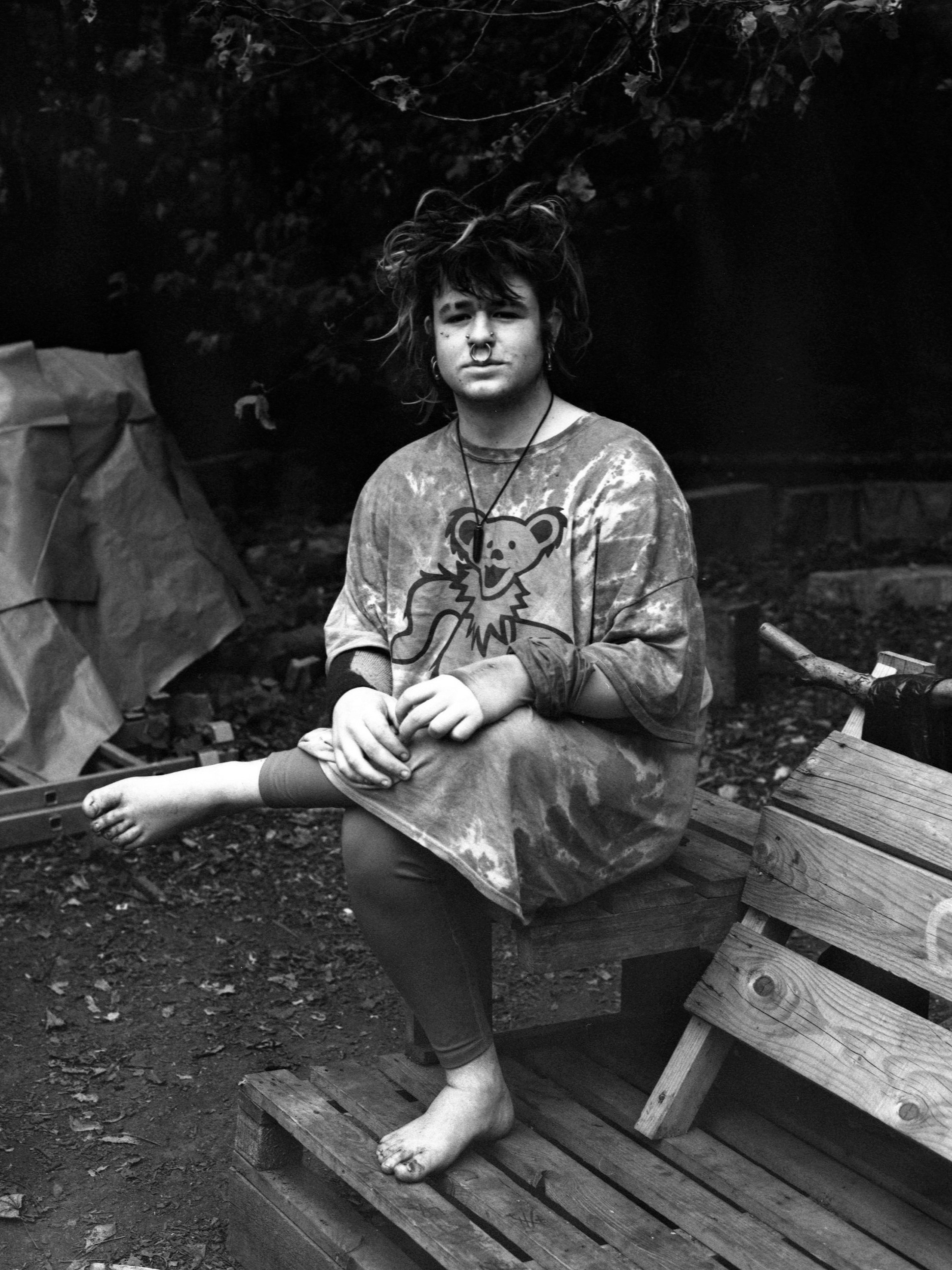

Grow-Decay

In 2010, a group of squatters settled in Sipson, West London, transforming a derelict plot into a thriving community market garden to oppose the construction of a third runway at Heathrow Airport. Operating as ‘Grow Heathrow,’ the group fought to preserve their self-built homes, hosting workshops and coaching sessions on land defense. They cleared thirty tonnes of rubbish, creating a self-sufficient greenbelt community that offered nature’s rewards. Residents built homes from trees, sold produce locally, and taught skills like bike maintenance and foraging, fostering resilience among Sipson’s community. Amid growing tension over airport expansion, the project Grow-Decay documented this five-year resistance. Through photography portraits, landscapes, and tools integral to their cause, the project captured the intersection of defiance and decay; offering a study of how grassroots activism and challenged local authorities, preserving a vision of environmental stewardship against industrial encroachment.

The Rain Came

Inspired by Irvine Welsh’s surreal novel The Acid House (1994), The Rain Came reflects a pivotal moment within the story. The protagonist, Coco Bryce, takes an unusually potent acid tablet just as a lightning strike occurs, causing him to swap bodies with the newborn baby of a middle-class couple, Rory and Jenny. The work focuses on the transformative moment of meteorological change described in Welsh’s text. By translating this narrative detail into braille, with the assistance of format provider Pia, The Rain Came creates a tactile and visual response to the written scene that bridges sensory experiences; encouraging viewers to engage with the text in a new, inclusive way, while emphasising the disorienting and surreal nature of Welsh’s story. Through this reinterpretation, the work offers a fresh perspective on the intersection of literature and visual art.

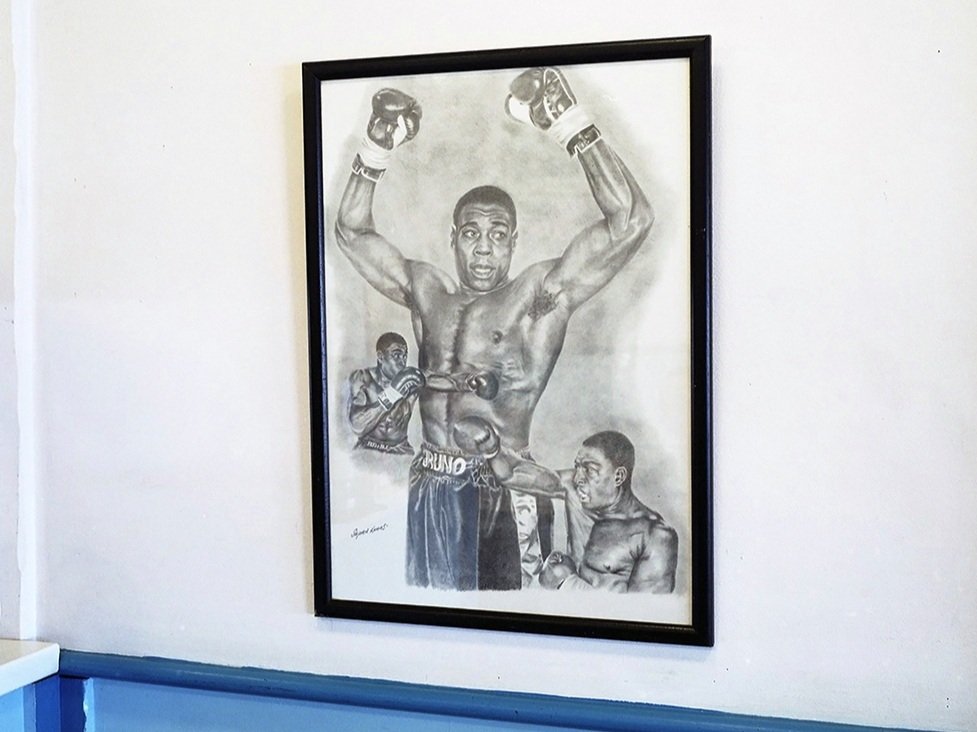

England, Half English

Published in 1961, England, Half English by Colin MacInnes (1914–1976) is regarded as one of the first post-war explorations of subcultural identity. The book comprises informal essays reflecting on English culture, multiculturalism, and the idiosyncrasies of everyday life. Drawing on MacInnes’s observations and the notion of partial belonging, the project England, Half English explores the complexities of fitting into a culture one only partially identifies with. It adopts an outsider’s lens to examine regional and cultural nuances, embracing clichés and stereotypes to provoke thought on English identity. Shot across various locations, the work blends romanticised and realistic depictions, reflecting both an insider’s and an outsider’s perspective. By positioning the photographer as a foreign observer in English spaces, the project delves into the interplay between perception, identity, and place, offering a layered exploration of what it means to be ‘half English’.

Stone Mountain

Stone Mountain examines the complex legacy of one of America’s most controversial monuments. The project utilises a collection of found postcards depicting the site, offering a unique perspective on a location steeped in history and charged with racial and cultural significance. Through these postcards - objects typically associated with tourism and nostalgia - an alternative narrative unfolds, one that contrasts the sanitised, idealised representation of Stone Mountain with its deeply problematic associations. The use of found images shifts the viewer’s focus, asking them to reconsider how the mountain, and surrounding location, has been commodified and presented to the public. Each postcard, often framed by the perspective as a distant observer, becomes a tool to interrogate the erasure of historical context and the glorification of figures tied to the Confederacy. In re-contextualising these images, the project encourages a deeper reflection on memory, identity, and the power of representation in shaping public understanding.

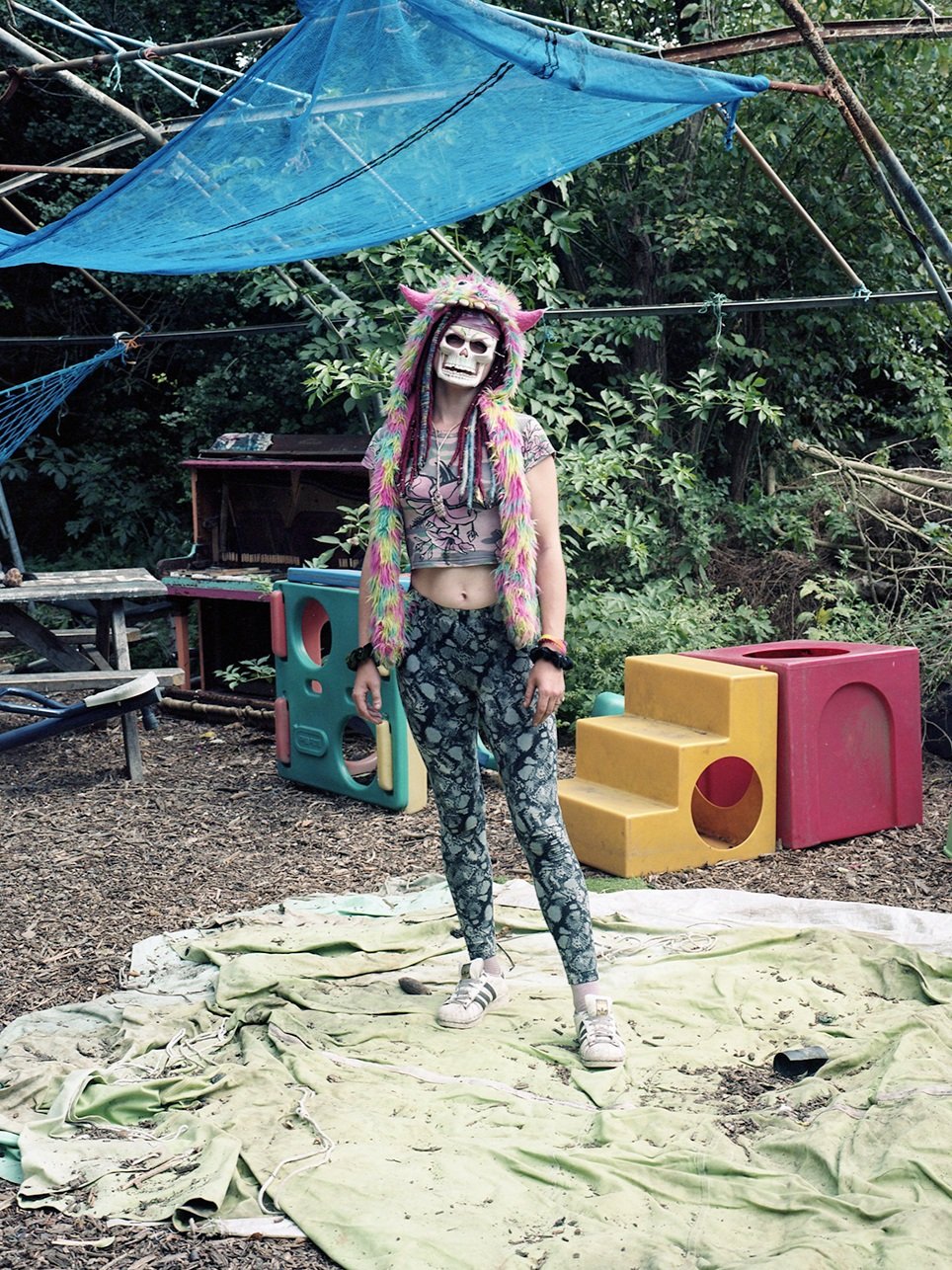

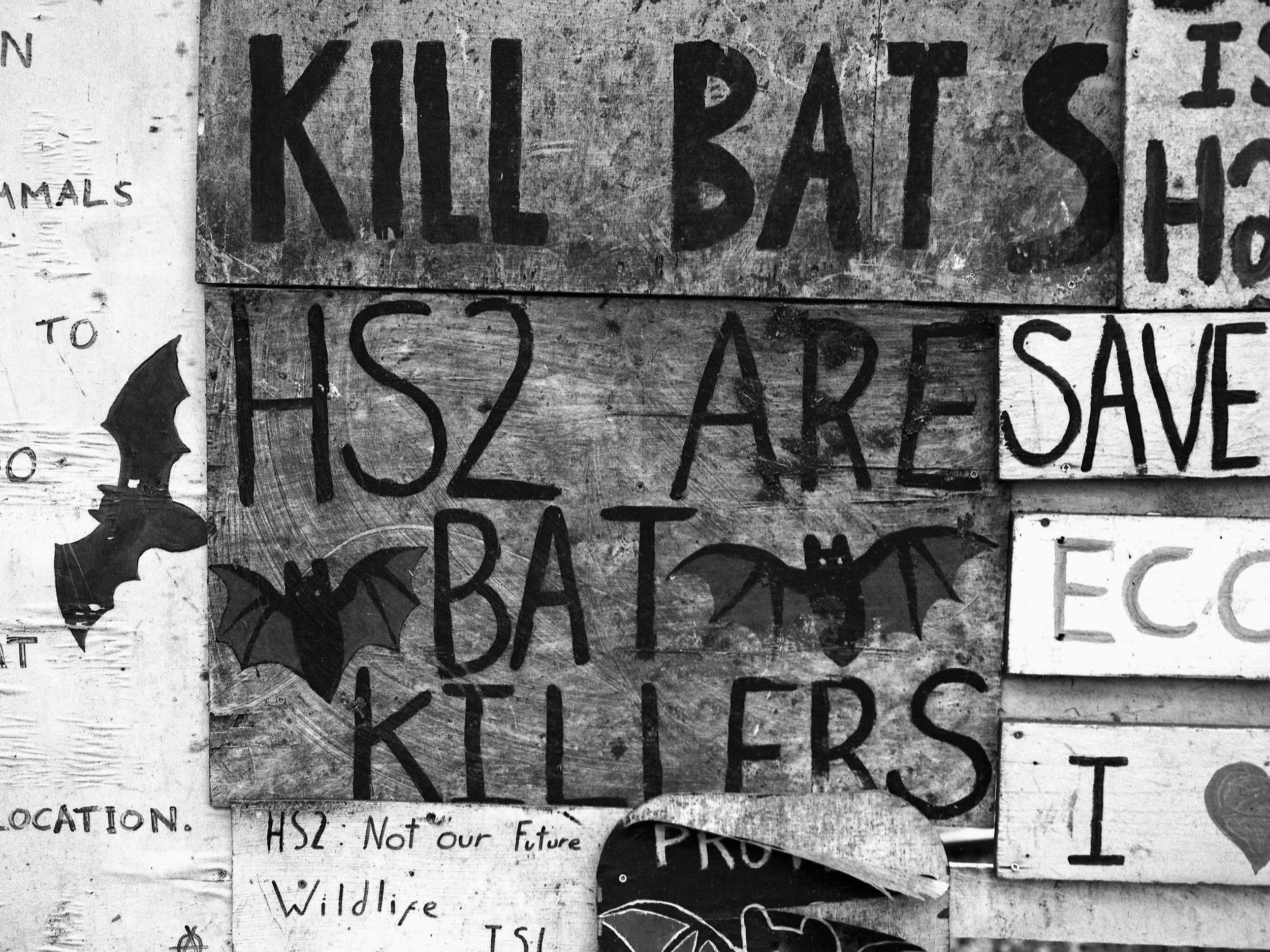

Not Our Future

The Wendover Active Resistance (W.A.R.) camp occupied a narrow strip of land between the A413 and the Chiltern railway line, south of Wendover, Buckinghamshire. Established to oppose the construction of the HS2 railway and its impact on local ecology, the camp was dismantled in late 2021. Activists built a tunnel, treehouses, and a 15-meter-high tower to resist eviction efforts. The photographic series Not Our Future captures the activists, their environment, and the materials used to champion their cause. Accompanying the images are banners, flags, and signs, which narrate the story of their protest. The work documents this recent chapter of resistance, shedding light on the creative and determined efforts of those who opposed HS2’s development. By preserving these moments, Not Our Future offers a compelling reflection on grassroots activism and its role in confronting ecological and infrastructural challenges.

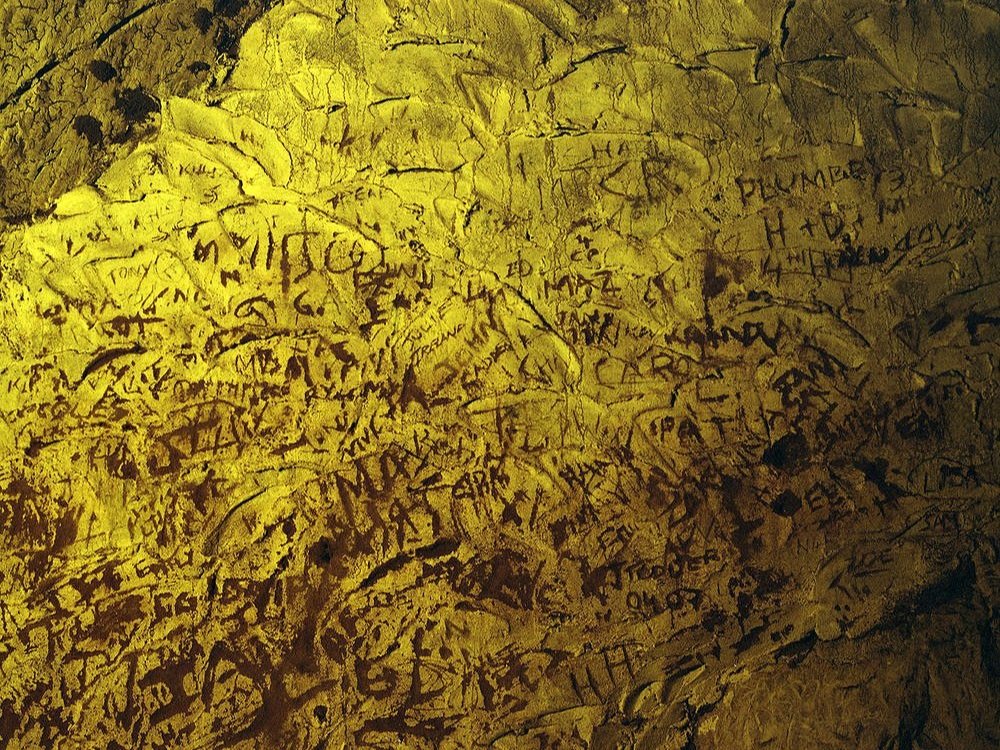

Police Harassment on Blacks

In September 1985, Handsworth, Birmingham, was alive with the vibrant energy of its annual carnival, a celebration of its rich cultural diversity. Days later, the same streets became the scene of the Handsworth Riots, sparked by the arrest of an African Caribbean man near Lozells Road. What followed was a night of escalating violence, with cars set ablaze, shops looted, and two lives tragically lost. Amid the chaos, a single photograph taken during the unrest becomes the focus of a powerful artistic intervention. Through the deliberate erasure of text graffiti - ‘Police Harassment on Blacks’ - left by a protester, the project interrogates and reconnects the narratives and historical accounts tied to the riots. By removing contextual details, the work challenges viewers to confront the void left behind - raising questions about whose voices are heard and whose are silenced. The absence of text invites a re-examination of memory, accountability, and the layers of meaning embedded in this moment of unrest.

Uncle Sam`s

A circus holds a unique, transient appeal - a constant structure transformed by its ever-changing surroundings. The project Uncle Sam’s explores this dynamic by documenting the subjects and British locations of the travelling Uncle Sam’s American Circus. The circus, with its obvious association to America, sparks curiosity, blending American cultural influences with a distinctly British context. Over three seasons, the project captures behind-the-scenes moments, offering an intimate glimpse into the lives of performers. Named after the symbolic figure of Uncle Sam, the circus embodies a mix of identities, cultures, and talents. Shot on KODAK film stock, the work showcases jugglers, contortionists, clowns, and highlights the seven Kenyan acrobats and a South American stunt team, emphasising their extraordinary abilities. The project reflects on the ephemeral nature of the circus, its spaces, and its evolving relationship with British audiences, celebrating a vibrant blend of performance and cultural exchange.